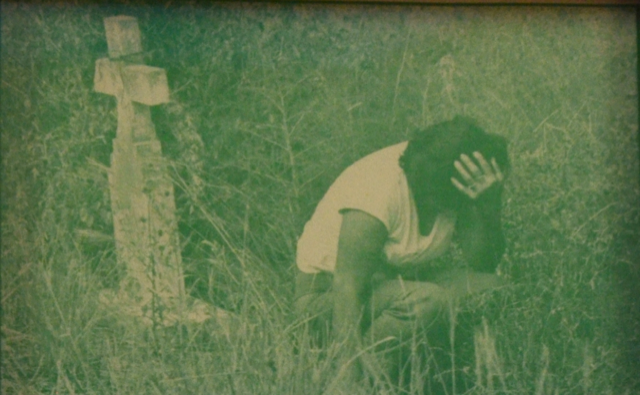

(Photo courtesy of LUPE | UFW)

Personal tragedy can dramatically transform a person’s life journey. That happened to Genoveva Puga, who, at 92 years, died late last month in a poor colonia in the Rio Grande Valley. The horrific death of her son changed her life in a way that bettered the lives of tens of thousands of Texas farm workers.

Her son Juan Torrez, in his early 20’s, was killed in 1977 while harvesting citrus for Donna Fruit Company. The company forklift malfunctioned as he was hoisting a large wooden bin, full of oranges, onto a flatbed truck. The half-ton bin fell back and crushed him to death. Juan died alone in the orchard. His body was not found until hours after his death. One can only shudder at the excruciating pain he suffered.

Mrs. Puga at the time was working as a migrant farm laborer out of state. She had spent – and was to spend — much of her life in the nation’s seasonal migrant streams and harvesting crops in the Valley.

The tragic news about her son’s death arrived late to Mrs. Puga; and, by the time she arrived back home, she learned her son had been buried in an Edinburg pauper’s grave. There is a haunting photograph of her, weeping at her son’s grave, when she finally located it. No parent wants to predecease a child; and, when fate dictates otherwise, a parent wants to bury their child, with appropriate religious and social rituals. Not being able to do so only deepened her agony and kindled her anger toward her son’s employer.

When she filed for worker’s compensation against Donna Fruit for financial support for Juan’s wife and their child, the company denied the claim, saying he was an independent contractor who had “volunteered” to harvest the citrus.

Indeed, that was the agricultural industry’s standard subterfuge: field laborers were not actual employees, but were independent contractors or working for one. Under Texas law at the time, agricultural employers, unlike most other Texas employers, were exempt from providing workers compensation, even though agriculture vied with construction as being the state’s most dangerous occupation.

This left local charities and already hard-pressed families with having to support injured, disabled farm workers and the families of those who perished. The Valley is already one of the country’s poorest regions without having this extra burden.

Mrs. Puga had had enough of this injustice and sued Donna Fruit. The trial judge threw out her case, which only made her resolve fiercer. She won in the Texas Supreme Court.

That judgment, though, only applied to her case. Far from satisfied, she set herself on the path with the local United Farm Workers Union, AFL-CIO to change the law altogether to protect her fellow laborers.

The struggle lasted seven years; and Genoveva Puga was at the forefront, organizing workers and supporters. Another lawsuit was filed, and the workers compensation exclusion was declared unconstitutional under the Texas Equal Rights Amendment; the judge ruling that it intentionally discriminated against an ethnic group, Mexican Americans. Then came the struggle in the legislature for a new statute.

She stood next to Gov. Mark White when he signed the new law in front of farm workers in San Juan, and she beamed a broad smile when both White and Lt. Gov. Bill Hobby spoke at the next UFW convention in Pharr, alongside César Chávez.

This petite, passionately-dedicated woman with a beguiling smile lived her heart and courage, and many thousands of farm workers, and the Valley economy, are much better off. Genoveva Puga is indeed the Texas Person of the Year in their book.

—————————————————————–

Harrington, retired founder of the Texas Civil Rights Project, was Mrs. Puga’s lawyer. He is now a priest with Proyecto Santiago at St. James’, Austin.